by Hardscrabble Farmer | Posted Oct 27, 2015

There was a hard frost last night coating every surface. Down at the trout pond a column of vapor rose straight up looking like a ghost at the edge of the pasture and you knew without having to open the door that it was well below freezing. The dogs stared in through the kitchen window awaiting their morning bones having spent a good part of the night trying to keep the black bear that has been haunting the orchard at bay. In the darkness you could hear them peel off from the house more than a few times, barking up a storm as they raced down the lane to the spot where the last of the apples covered the grass. We got together with our friends on Saturday to make cider, the kids climbing the trees to shake the branches while the sweet, swollen globes fell like rain onto the tarp. We gathered a couple of tubs full and ground them in the press, a variety of Pippins and Baldwins and Burford’s red flesh, each with it’s distinctive flavor. The sweetest produced a lighter cider, the color of fall leaves and the sour looked like maple syrup, light and clear. We mixed five gallons in a carboy to make hard cider and when the kids went inside for supper my friend and I cleaned up with icy cold water in the darkness next to the sugarhouse. By the time we got into the kitchen our wives and children were dishing out our meal, the aromas filling the room with the smell of apples and pork.

My arm has been troubling me the last few months and lately it has gotten worse. I don’t have the option of giving it a break so I work through the pain as best I can so I can finish up the last section of fence before the ground freezes. I understand that as you get older all of your past injuries pile up on you and deliver a different kind of discomfort that you have to learn to live with, like the lines on your face. Behind the house where the old electric lines came in there is a sort of tunnel that had been cut out over the years by the utility company, straight along the bottom edge of the sugar orchard. The majestic rock maples and old growth ash rise like columns along the boulder strewn edge of the property, but you can see where the limbs have been cut back over the last century to make way for the black ropes of electric lines. Above the top end of the pathway about sixty feet up the east facing leaders have done something I hadn’t really noticed before; each main limb has turned itself in a graceful curve upward, one tree after another, like ladies hiking up their dresses to keep them from getting wet. Somehow these ancient trees seemed to know that in order to avoid the arborist’s saw it must turn away, contort itself to save it’s limb. I took note to check other trees around the property for a similar trait but haven’t found another example anywhere. They changed because of their history, because of past injury, into something different from all the rest.

A healthy sugar maple grown in perfect conditions is one of the majestic treasures of Nature. It rises from a solid trunk some thirty feet or more before it heads out in a series of healthy leaders, each producing a profusion of side shoots that culminates in a spreading, leafy head that resembles a tulip flower. If two or three maples grow close to one another, they each occupy the space as if it were — viewed from a distance — a singular tree. It is their nature to fill as much space as they can in order to maximize their leaf production. The side benefits to us, of course, are the blazing display in Autumn and the delicious sweet syrup in the Spring. For the tree it is to make other maples. Ironically some of our top producing maples — in terms of high sugar content sap — are the gnarled monsters that grab onto the boulders with roots like an old man’s hands. With luck they can outlive human nations on a time scale that rivals Methusala.

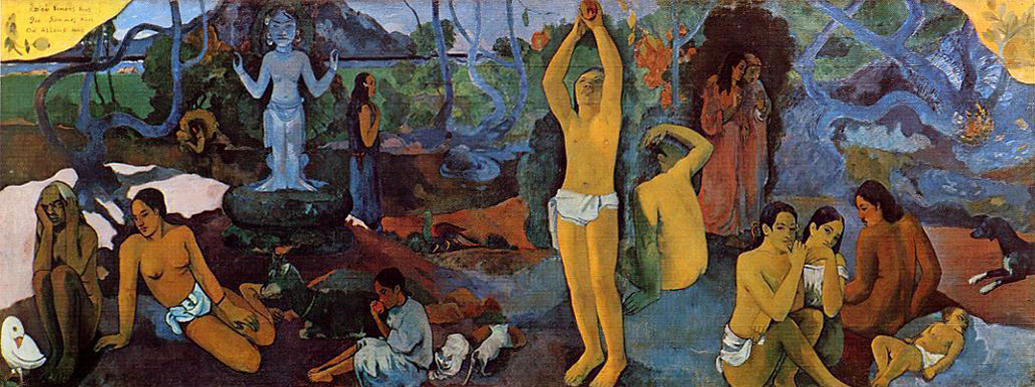

When I was a senior in high school I applied to one college, Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. It was my dream, back then, to become a painter. I was one of the better artists in my high school and I was passionate about painting and drawing, spending countless days of my life doing still life and landscapes when I should have been doing other things and the more I worked at it, the better I got. Part of the entrance application was to produce a self-portrait. For some reason I decided to draw my foot using a number 2 pencil on paper. I was accepted despite my less than orthodox submission and that drawing remained in my personal collection for years. I thought of it the other night as I was laying on our bed after a shower and I looked down at that same foot through the less focused eyes of a man thirty five years older. The little toe had turned under the end of my foot from the hundreds of thousands of miles it had walked in the intervening years and it had lost all of the youthful definition it had once had. No longer graceful in design, but just as functional as ever I was grateful for it’s service, both in getting me into Art School and in walking me down the countless paths that made up the journey of my life, even if it was old and ugly. For some reason I thought about the maples behind the house.

My son has come by the house to visit a couple of times in the past month, something I enjoy very much. He likes to talk about what he’s reading — Fight Club, Atlas Shrugged, Down The Shore and The Unbearable Lightness of Being are his most recent purchases, all from the used bookstore in the next town. We discuss whatever is on our minds and I realize how much I miss him being around, but am pleased that he is as independent as he is at such a young age. On his last visit he brought up his concerns about the meaning of life — where we go when it is over, why we’re even here and in his comments I can hear some of my old beliefs about such things and I tell him that it’s part of the growth process to consider things we can never know, like exercise for the body, pondering deeper thoughts stretches the limits of the mind and makes it stronger. I get that he isn’t really looking for my answers but trying to formulate his own and using me as microphone to articulate these thoughts out loud. What he doesn’t know is that his questions have moved me to think about things I had long ago put away as I moved on through life to other ends. I no longer paint or draw, except when the younger children ask me to, and though I recall what that passion felt like, it isn’t there anymore. Life changes you no matter how hard you try to change your life and eventually you become what you are through a combination of outside influences; what you eat and what you do, who you love and who loves you. How we accept or regret those changes doesn’t really alter the outcome, only the degree to which we succeed or fail in the present. I know that my son will not find the answers to the questions that he is asking, but it is the fact that he is asking that makes me believe that he will do well in life. That curiosity is the engine behind the quality of life he’ll likely lead and as I watch him speak I study his face and his hands I see him becoming the man he will likely be in the future, speaking to his own son one day.

It’s full light out now and the house is quiet. Everyone is off doing something and I have two coils of high tensile wire left to pull with my bad arm and my old feet, but I am confident that I will finish up the job ahead of the frozen ground and with some time to spare. By then the cider will have fermented and the last of the waxy leaves will have fallen from the maples out back and it will be a treat to share the products of those old trees no matter how gnarled and twisted they may be. Sometimes it takes a lifetime to figure out why we we’re here and what we’re here for, but there is a reason and even if we don’t see it ourselves, you can believe that somewhere, someone else will.

No comments:

Post a Comment